With me in my 60’s and Covid-19 blowing on the breezes, I’m not going to allow a lot time for grass to grow between my toes. I could have roots growing through my corpse before I know it. So, I’ll be moving right along at expressing what I think in broadest, general, sub-academic terms. But I’ll at least get it expressed at some level.

In post # 3, “Rights 2” I shared about a meeting with a Christian mentor on the topic of homeschooling and family liberty. That meeting marked the start of the unraveling of what I now view as my “American Civic Faith.” Once getting the American Civic part of it out of the way, it was much, much easier to find at least some variety of a biblical Christian Faith, however lacking it may be. It’s a Faith still far more worth keeping than the American Civic Faith I once had. Or at least I have come to think so. I didn’t get all that American Civic (rights based) Faith nonsense from my parents. They raised me on bible teaching. I got the American Civic Faith part of it from the thorough brainwashing of compulsory public education in tax funded schools. Those schools have only gone downhill since. And what I got was plenty bad enough.

We are now so submerged in enlightenment rights thinking that we are drowning in it.

If you tried to research “ancient modern science” there’s just not a lot to be found, maybe an occasional blip anomaly, and that’s about it, if that much. Modern science isn’t ancient. Almost end of story. You won’t find it “back then,” anywhere much before the enlightenment explosion of science. Go back any further than that, and there won’t be an awful lot to be researched.

Well a little less concretely, it’s similar with trying to research “ancient modern rights thinking.” We’re reading all history through our enlightenment-modernized hyper-righted lenses. We look to see things even similar to modern rights (rights as we see, know, and understand them), even early rights, in lots of places the ancients may not have seen them. Like modern sciences, anything like our conceptions of individual rights just wasn’t here yet. Our modern, Western minds are so thoroughly rights inebriated it is almost hard for us to imagine a largely pre-rights world, and to grasp just how “modern” or recent our conception of “natural rights” really is.

Enlightenment recency of rights thinking. Even as we read the ancient literature, we read it through our own rights-lenses, or almost rights-blinders from which the ancients did not suffer.

Backwards through rights time:

Our present legal system is such a sociological train wreck that it is at least as worthy of dismantling as it is of research. Our natural rights based legal system was our mess to make, and it’s our mess to take apart. And take it apart we should, but not before we have something better with which to replace it, an allowance wisely provided for in our own constitution. I’m not going to invest much effort into unraveling present legal theories because I see them as problems we’re all so familiar with that we can barely recognize them as a problems. Suffice it to say, they presume rights-in-the-first-place. And that’s where they go wrong. So, whatever they’ve done with that is what’s yielded the mess we have. I don’t need to know an awful lot of what it is. I’m living it. And it works well only for the people who most directly live off of it.

The whole notions of “natural rights” from which so much of our present nonsense derives all originated very recently in human history – about 300-400 years ago – way after the close of any biblical period. Backing up to enlightenment rights philosophy takes us primarily to the influences of the philosophers John Locke and Thomas Hobbes. These are the Founders of modern philosophical natural-rights-oriented thinking. In much the way that “modern science” largely originates with the enlightenment period, modern rights thinking also originated about then. Much prior to that, and rights were a thing stemming primarily from deity or deities, and were sorted primarily between royalty and nobility. Earlier rights were either human claimed as proclaimed and distributed by deities, or claimed by people based on their claimed or presumed relationships with deities. If you go back prior to Locke and Hobbes, and look for deity-free “philosophies of rights,” there’s not much to be found. Even Thomas Jefferson picks up on the notion of “nature and Nature’s God” as rendering certain wished for rights and realities s as “self-evident.” More of a declaration than a persuasive philosophy.

So, for Locke (1632-1704) Hobbes (1588-1679) and Jefferson (1743-1826)

It’s been between 35 and 40 years ago that I actually studied John Locke’s political work. The take away at that time is the one I carry today: I dismissed it as a train wreck of internal inconsistencies. If the internal consistency of a position was the gauge of its influence, then the influence of Locke is almost unimaginably out of proportion. And, this largely by way of the American Founding Fathers. Not many years after my study of John Locke I began studying the philosophy of B.F. Skinner (whose direction I do not generally like). If internal consistency in one’s work is the comparative standard, B.F. Skinner makes John Locke look like a juvenile delinquent wanna-be philosopher. For those of us who don’t like Skinner’s approach, his internal consistency can be almost infuriating. By a standard of internal consistency, amazing work. It may be that Skinner’s influence has been out-proportioned on those grounds alone. And maybe almost justifiably so.

I’d like to like Locke’s work for the same reason everyone else liked it. It wasn’t popular because it was good philosophy, or even internally solid. It was popular because it was populist. It’s what people of a key time and place, evidently Thomas Jefferson of the English Colonies in particular, wanted to hear. In light of that, the fact that it also happened to be lousy philosophy just didn’t pose much of an obstacle.

I’ve never studied the natural rights philosophy of Thomas Hobbes for myself. With only the most cursory review of reviewers, it seems to me that people familiar with the intricacies of Hobbes may well find my thinking more related to Hobbes than Locke. Without even being well informed, I’d nearly hope my own work was closer to something, nearly anything other than Locke.

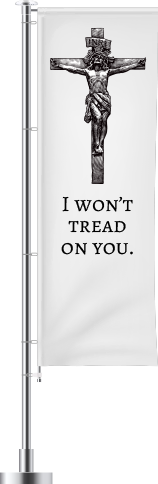

By way of the since evolved “God & Country” ethic in America – Locke, by way of Jefferson, and Jefferson himself have been elevated to a very nearly biblically authoritative level of writers. Well – in both cases I think not. Not even close. We kind of tack the American state papers onto the Bible – and THAT becomes our “God and Country Faith” – the American Civic Religion. As I think I’ll be able to indicate with reasonable clarity, the Bible overall and the founding American paperwork don’t fit together all that well. And, so far as I can tell, one key difference centers vastly around rights thinking, prevalent in the American papers and experience – barely existent in the Bible.

Some may protest “but the biblical documents were largely pre philosophy, so pre-rights” – And that’s largely but not entirely true (it would be easier for me if it was entirely true). But just because a thought train gained most of its traction much later in history doesn’t make it anymore correct. There have been plenty of bad ideas in the past 2,000 years. The vast expansions of rights thinking may have been one of the flawed directions.

Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) & Magna Carta (1215-1297 and following)

The Magna Carta was first signed in 1215, as somewhat of a peace treaty between the King and the Barons. The agreement quickly fell apart, and was basically annulled by the Pope a couple of years later. There was more warring, and a couple of Kings later, in 1297, the Magna Carta finally became the Law of the Land. Well, this time period from 1215 to 1297 more than encompassed the entire lifespan of Thomas Aquinas. The Magna Carta was 10 years old when Aquinas was born, and didn’t become the Law of England until 23 years after he had died. So, there’s 100% overlap in timeframes there, but the Magna Carta situation was playing out in England, and Aquinas was working in Paris and Italy. I’ll begin with the Magna Carta, then move to Aquinas.

Some rights-oriented chronologies will pretty much skip back from Locke and Hobbes to Aquinas, and all but ignore the Magna Carta. I’m surprised that more of them don’t point to the Magna Carta. If they’re looking for organized thinkers or scholarly contributions, that makes sense. But the Magna Carta was also largely drafted by one man, The Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton. I confess to being largely ignorant of the specifics of the Magna Carta. Online there seems to be a fairly standardized approach, with the same text being repeated from Wikipedia to the descriptions of related books listed on Amazon, and even the backs of book jackets, or back cover descriptions of books available on Amazon.

There are a couple of things I can take away from it all. One thing is, again, that this whole conflict being settled between nobility and royalty goes back to a “redistribution of Divine Rights.” The Catholic Church, by way of the Archbishop of Canterbury, is trying to re-broker the lines of divine rights between royalty and nobility. The Magna Carta wasn’t really about ordinary citizens, and individual rights, but a peace treaty between nobility and royalty. It seems to me, mainly seeking a degree of predictability in governance as much if not more than anything else. It looks to me more like a founding contribution to the notion of “rules of law for the rule of law.” In other words, a set of rules about how rules, and even which were to be made and enforced. In other words, for Europe anyway, the grounding of Constitutional systems. To me, the aspect or notion of a set of “rules of rule” seems more important than what the particular rules may have been. But I don’t think this idea of “rules for rule” would have been an alien notion to the Greeks or Romans, centuries earlier. But the Magna Carta does seem, almost by historical default, to have been a fresh re-introduction of those concepts to modify Divine Rights between the royalties and nobilities of Europe.

Now, it’s just impossible to overstate the influence of the Magna Carta, and the resulting evolved English system of governance (parliament), on the entire American Founding set of events. We were British Colonies, and our Founders were British Colonists. Up until Independence, the British system was ours, and we were its. All this tradition and history being discussed was our own history and tradition. We had no separate national identity. We’re talking from the early 1215 to the Declaration of Independence, in 1776, over 550 years of evolved common tradition between the first signing of the Magna Carta, and the U.S. Declaration of Independence.

Concerning my discussion here, modern, Enlightenment notions of rights, individual rights in particular, here is the most fascinating thing I have discovered about the Magna Carta and its American aftermath. By the 1600’s to 1700’s, the Magna Carta is already several hundred years old. The Magna Carta had really been a powers-settlement document between the rights of ruling classes, royalty and nobility. Ordinary citizens and the issue of any kind of individual or human rights for anyone less than nobility had not factored into it.

Here’s a bizarre thing: by the 1600-1700’s there had developed a false mythology about the Magna Carta itself. The mythology had something to do along these lines. Perhaps in trying to “re-discover,” “make-up,” or otherwise legitimize claims to individual human rights,a mythology developed that the known Magna Carta was actually along the lines of the Magna Carta.2. The mythology held that prior to the known Magna Carta, there had in effect been “the original Magna Carta,” or Magna Carta.1, but that it was long since lost to history. That Magna Carta.1, so the mythology went, had in fact recognized individual citizen, human rights. So, in much the same way that current rights theorists and developers like to preface their claims with “this new right is not a new right, but one that has always existed unrecognized (kind of like they were “discovering” a new law of gravity), the mythology surrounding the Magna Carta sought to legitimize or lay newly rediscovered rights for individual citizens’ rights.

Now again, by the time of the signing of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, the Magna Carta is 500 years old. This false mythology concerning Magna Carta.1 had developed relatively late in that interim. Hobbes and Locke were both English. Jefferson and the Founding Fathers were all English. This false mythology of individual rights from Magna Carta.1 may have had only weak traction at the time of Hobbes (1588-1679), but gained steam by the time of Locke (1632-1704). In other words, this false mythology was contributing to the senses-to-be-made in philosophy, or English philosophy and tradition, hence, what would become U.S. philosophy and tradition. Certainly, by the time of Jefferson, in the way that Locke’s philosophy was crummy but populist, this whole set of false mythology surrounding individual rights in Magna Carta.1 was outright FALSE but popular because it was populist. And its impacts were made outrageously influential through Jefferson and his Founding Friends, by way of the American Founding paperwork.

There has been more than one set of “citizen’s rights” thinking in Western history. The Greeks and Romans, at least, came before Archbishop Langton and the Magna Carta. (And as we’ve seen, individual rights are not what Archbishop Langton was up to anyway.)

But here’s the thing: earlier in this series of posts, in musing about the whole present, American (and Western) sociocultural mess of rights, I wondered “What the hell is it about rights in the first place, anyway?” This is bizarre to me – I promise – but OUR present context for “individual rights,” In other words, our “individual rights in the first place,” descend most directly from a since debunked false mythology surrounding the Magna Carta.If anyone is still bothering with any attempt to support “divine origin” (Nature and Nature’s God, per Jefferson) for “individual rights,” this seems to me to be an exceedingly lame claim to legitimacy. I almost want to be sorry for how weak this claim is. I mean, it’s in support of the overall argument I’m making, but it just has to be a pathetic recognition for any opposition. It strikes me as an utterly merciless, intellectual defeat. I didn’t even start out hoping to find anything this good. Amazing what a little homework can turn up, and relatively little homework at that. Maybe a day and half worth. There’s the head, heart, and soul, of our present legal system and its claims to intellectual legitimacy for its individual rights based sociocultural train wreck. It’s not even a mythology surrounding a false deity, but merely a false mythology about a plainly enough historical document, a false mythology surrounding a peace treaty drafted by an Archbishop. Wow. Pathetically weak claim to any intellectual legitimacy for individual human rights.

As I write this, the United States has a President who seems to the Presidential Hoax-Meister. Every time you turn around, he’s alleging another Hoax of one kind or another perpetrated against him. Since he’s brought us around to the topic of Hoaxes, boy, have I got one for him!

At the beginning of this post I said I wouldn’t bother researching our present legal theories because they presume rights in the first place. Well here are the rights they presume: rights from false mythology surrounding the Magna Carta. That could almost be ‘nuff-sed. But we have some history left to cover, with more ideas to interject along the way.

In the meantime, Jefferson’s U.S. Declaration of Independence is not so much a masterpiece in the philosophy department of rational persuasion. It’s more of a verbal tantrum thrown at a King, one along the lines of “This is how we’re going to have it be, or else.” And surprise of surprises, the King to whom it was addressed chose the option, “or else.” A war was had. The Colonists won. And much the rest is history. Including a global, sociological pandemic of individual rights thinking.

Next up, a briefer (I hope) consideration of Thomas Aquinas.