Rights

OK, maybe literary license, or maybe just plain leading deceit. But I do promise you this in all seriousness: not nearly so many rights here as you might expect, and probably not the ones you would guess. In the end, evidentially and biblically, we will arrive at 2 absolute rights (evidence based, and not contradicted by the bible) and 1 potential right (biblically based).

It’s funny how people generally don’t question things unless or until we have occasion to be unhappy with them for some reason. Most people are happy with their rights. Or, if unhappy, they’re unhappy only in the aspect that they want even more of some kind of rights. Nobody in my time and place seems to question the very foundations of “rights in the first place.” Nobody much pauses to wonder if our whole notions of rights are even appropriate human social constructs to begin with.

I have had a more-frequent-than-realized application of having another’s rights being used against me, to prevent me doing the moral and ethical things that ought to have been done. In other words, I have had life experience that has given me pause to back up and wonder about “rights in the first place.” This is not my own life example, but another example that’s even more common than my own: in some divorces the “rights” of a parent weaponizing the children and parental child-access are put before the actual well-beings of the children. The “good parent” with children’s best interests at heart (the one not weaponizing legal child access) confronts exactly this excruciating dilemma: responsibility for the children’s best interests or responsibility to the rights of the weaponizing parent? We know how our courts all too often decide this moral debacle. Rights are frequently problems in human social intercourse, all too often leading to real moral dilemmas, rather than helping to solve them.

That an evolution of “rights thinking” has been in progress for at least 3,500 years in the Western traditions, and no one has yet approached a consistent philosophy or theory of rights, might be another telling aspect of a rights-oriented paradigm for human social intercourse.

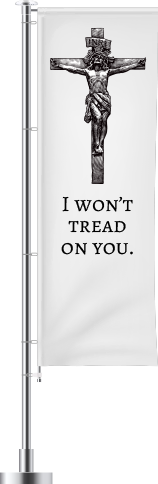

One complication with rights as historically and presently conceived is this: they are fundamentally a social construct of “against-ness.” In other words, rights are construed as claims and demands people are entitled to make, demand, and enforce against other people, all too often by way of government coercion or outright force for enforcement; rights brokered through government. For a society that lays claim to being civilized, to have such vast swaths of our social intercourse administered through the gun sights of government seems – socio-culturally inept, at best. These may be early clues to the thought that rights (as currently conceived) aren’t leading anywhere worth going. Rights provide the paradigm-defining foundations for sociopolitical philosophies of inter-human against-ness. Likewise, any sociopolitical philosophy or legal theory founded and grounded on rights may accordingly be suspect in its capacity to get us anywhere worth going.

While we have a long way to go until we arrive there, I will give away this part of my conclusion now, just to nip any thoughts of anarchy in the bud. No anarchy here. And that’s no misleading hook. We can and must arrive at law and order. But we don’t arrive there by way of anyone’s rights. We get there by responsibility. The questions for law and order become, “What are the human responsibilities’?” And “Which failures of personal, human responsibility are we going to prosecute in the public circles?” This will be my proposed path to law and order.

Disclosure: trained competence lacking

Beyond a level of U.S. high school, I am not trained according to any scholastic or professionally recognized academic template. I’m an autodidact. My background in these arenas does span a lifetime of 60-ish odd years. I was raised in a decidedly Christian sub-culture. As I emerged from my early Christian cocoon out into secular collegiate society, I was more directly confronted with “the rest of the real world out there.” My earliest recognized key challenge concerned how to handle the evident contrasts between creationism and evolutionism. Since the background I had in tow was biblical, I decided to start with “What to do with the bible and its take on creationism?” then move as necessary into investigations of evolutionism. A couple of upcoming posts will better explain “what I decided to do with the bible,” or how I decided to handle it. But for application of this post, I will share that I began my bible inquiry with an attempt to understand ancient Hebrew mythology within a context of its competition at the time. Not my time, 35-40 years ago, but the sociocultural context from which that mythology had originally arisen. I wanted to get a general sense of comparison and contrast, to see if the Hebrew mythology had a different look or feel to it from the many other competing mythologies of its own time and place. Were there common themes, if so, what were the variations in expression, and what were the similarities in themes? If the Hebrew mythology seemed to be about anything decidedly different (aside from Monotheism) what was it? Part of what I was looking for was “What sense did this material make to the early listeners and readers back then?” And, “If the Hebrew mythology made different kinds of sense than was typical of that time and place, what were the differences?” I did not study any one set of ancient mythology with any focused academic rigor, not seeking to be an expert any one or more of them. I was just wanting an “overall sense of the competing mythologies of the time,” kind of like a survey course might offer. For me at the time, no small part of all this was the quest to understand, “What sense did the early Hebrew creation mythology make to the people who made it up?” Or, “What sense were they trying to convey to the people of their own time and place, and how did that contrast, if it contrasted, with the competing senses on offer at that historical context?” Put differently, let’s say that 2,700 to 3,100 years ago, ancient Hebrew creation and creationism was not competing with the evolution and evolutionism of my own time, but it was probably competing with other creation related mythologies of its own time. What were those mythologies, and what were the similarities and differences between them and the Hebrew stories? What were the comparisons and contrasts? I thought this study might be revealing, and it was. Enough so that by the time I finished, I didn’t worry so much about any perceived conflict between Hebrew creationism and evolution. I was then able to confront and deal with evolution without much apprehension or personal stress. (Evolution-ism is another, bigger topic, but not for here.)

But following this course of interest, I reviewed Egyptian, Sumerian, Babylonian, Canaanite, Akkadian, Hittite, Assyrian, and other Mesopotamian mythology. Admittedly, I was not focused on legal codes, but creation and most directly related mythology. I did not directly pursue legal codes except by happenstance overlap. I did read the code of Hammurabi, and did review the Gilgamesh Epic and some other less-direct-creation-related stories, mainly because the cultural overlaps seemed so significant. Also, of long remembered interest, I did manage to get captivated by the Enuma Elis, and discovered – at least to my own amazement – that I found it to be an early example of what I guess to be an undercover (at the time) monotheistic document.

So, from a period of investigations ending 35 years ago or more, my sense at the time was general and vague, and has since had 35 plus years to grow even more so. That’s admitted.

Much of this background shared above is intended to indicate some of my general approach to investigation, but also to admit this lack of precise clarity on the topics at hand.

Back to rights thinking

Not having focused on ancient legal codes per-se, nor the relation between those codes and their mythological connections (or not) to the “gods,” I can’t lay claim to the thought that “rights thinking originated in ancient mythology.” In other words, I do not recall reading any “divine proclamations of rights, assigned from the gods to the rulers” or anyone else.

And yet, a common theme or feature of the societies at that time and place does seem to be that the rulers claimed authority to rule based on either on their very own divinity, or in other cases, that the rulers were descended from or partly descended from the divinities in their mythologies, as a distinct class of gods or human-god mixes, apart from the “ruled, mere mortal masses.” I can’t say that the authors of the early mythology put those “rights-of-rule” into the mouths of their god-characters, and had those god-characters issue the rights to the rulers.

But it does seem evident that, generally speaking, one way or another, the rulers in many if not nearly all those societies came to claim their rights to rule based on claims to their own special relationships with those mythological gods.

This was one of the aspects in which Hebrew mythology, or at least its applied sociopolitical use seemed to be a standout, though it didn’t really command my attention very much at the time.

But if like me, you’re a little skeptical about the ancient gods (and the contingent ruling classes and their divinity-based claims of legitimacy) in the ancient Near and Middle Eastern mythology, then we might want to back up and reconsider the inherited rights paradigm. So far as I can tell, for the Western thought traditions, rights thinking seems to have started just about then and there, with rulers of divine origins having divine-ruling-related rights over the ruled mere mortal, all the rest of us.

Just for the 4,000 year stretch of the imagination, it has this feel to it, or a perhaps-evident sense about it: Entirely human rulers claimed ancestry of the gods as establishing their “rights” to rule the merely mortal ruled. As they grew city-states, and amalgamations of city-states into empires, they needed expanded “ruling classes” to administer ever expanding empires. So, “rights of rule” were shared and disseminated to expanded ruling classes, who were delegated ruling “rights” over expanding masses of the ruled, in conjunction with “responsibilities” to the higher, divine or divine related rulers. And through, say, 5 generations per century, for 40 centuries or so, so 200 generations later, we end up with modern human rights philosophies and theories, sociopolitical and legal, such as they have accrued over time; all descending from these early claims regarding these divine rights of rule from the gods of ancient mythology. And, this being the case whether the gods mythologically, explicitly assigned the rights to the ancient rulers, or whether the ancient rulers merely self-ascribed the ruling rights from the gods for themselves.

As one early note to it all, I will say that there is a notable dearth of Hebrew contribution to rights related religious or philosophical development over the course of history. Western rights thinking has evolved sporadically at various times and places, with contributions from various societies and cultures. Early Hebrews and later Jews are just nearly absent from the field of rights thinking. The God of their mythology did seem to have some different socio-political, ethical, and human moral implications in relating to one another as humans, whether as rulers, ruled, or just average folks trying to get along with each other.

But based on the above assessment, it seems to me that “rights” were initially, and most likely tools of psychological and emotional class warfare, for use by the rulers against the ruled. From their very inception, about human “against-ness” (under the pretext of ruler’s divine against-ness to those mere mortals being ruled). In short, for now, I will say the Hebrew mythology in the bible does not seem to set up that situation, and historically does not seem to have been used to those sociopolitical or cultural ends.

A Broad, Short Sweep

But in the broadest, shortest sweep I can deliver, it seems rights thinking started with this connection between ancient rulers and the gods of their mythology, primarily as tools of psychological and emotional class warfare of the rulers against the ruled. 4,000 years (200 generations) later in the West, we have evolved rights thinking to the point of “individual human rights.” In our present scenario, each human is a class against all other humans, for psychological and emotional class warfare of one against all and all against one. This class-of-one warfare is still most conveniently brokered through the gun-sights of government, though perhaps government not quite so divine in origin as was once conceived.

And for all that, in the name of a supposedly civilized people, we end up with the sociocultural, political, and legal morass that is 2020, USA.

As an end-note to this first post on rights thinking, I add the following teaser: While rights thinking may well have originated with the gods of ancient mythology, notwithstanding potential confusion on the parts of Mr. Jefferson and some of his Founding Friends – so perhaps contrary to what we Americans have been taught and like to think – maybe rights thinking has not originated so much from the God of Judeo-Christian, or biblical tradition.

My next post should continue with rights thinking. I will share a little of my background research on the development of rights thinking – touching on a few key points (very few) of that 4,000-year broad sweep I offered just above.